Article en français

SS CYG – UGSS

SS Cygni is often called the "Queen of Cataclysmic Variables." As the prototype of U Geminorum-type variables (UGSS), it is the perfect laboratory for understanding the physics of accretion disks.

Since its discovery in 1896 by Louisa D. Wells of the Harvard College Observatory, SS Cygni has undoubtedly been one of the most observed variable stars in the night sky. In the century since its discovery, not a single one of its eruptions has been missed. Nearly 220,000 observations, submitted by AAVSO observers worldwide, have tracked some 800 eruptions. As the brightest star in its class of dwarf novae, SS Cygni is undoubtedly a favorite among many observers.

It belongs to the U Geminorum (UG) family of stars, which have three types of light curves: UGSS, UGSU, and UGZ. As you might have guessed, SS CYG is a UGSS type object, of which it is a perfect example. Its apparent magnitude varies between 7.7 and 12.4 according to the AAVSO, and we can expect a recurring event every 4 to 10 weeks, lasting 1 to 2 weeks. It is still relatively close to us, at 90 to 100 light-years from Earth (Burnham, 1978).

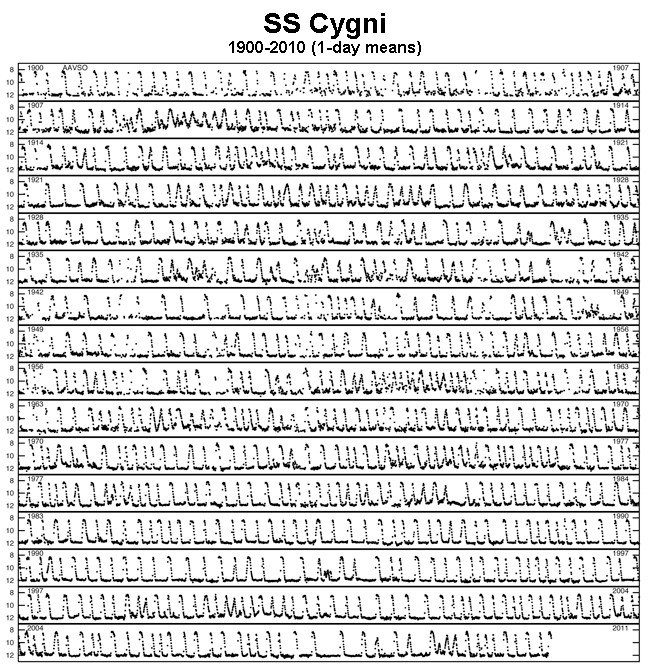

Figure 1 : Courbe de lumière de SS Cygni montrant l’alternance d’éruptions larges et étroite. Gracieuseté de l’AAVSO.

Description

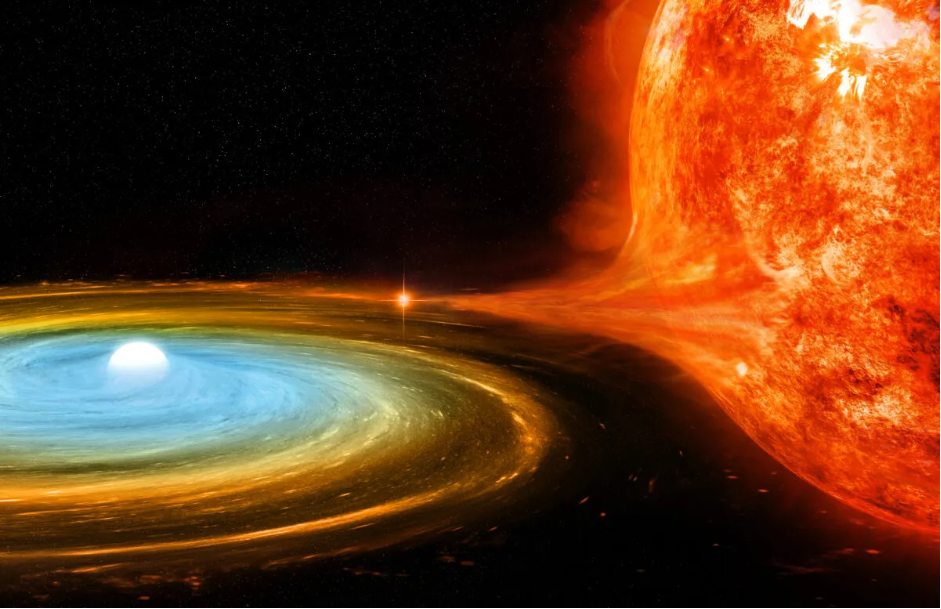

This is a cataclysmic star composed of a red dwarf and a white dwarf. According to some studies, their distances are very small, approximately 160,000 km and perhaps less, as they complete their orbital periods in only 6.60312 hours (0.2751300 days). The system's inclination has been calculated to be about 50 degrees, resulting in respective masses of M1 = 0.60 solar masses and M2 = 0.40 solar masses (Honey et al., 1989).

Cataclysmic stars always operate according to the same principle. A donor star, usually a red dwarf, "gives" matter to a recipient star, most often a white dwarf, which receives the matter in the form of an accretion disk, as it is unable to assimilate it. The result is that it fills its "rock lobe" until it is saturated. When saturation is reached, the pressure and temperature increase until an eruption is triggered. It should be noted that a small amount of material is still received by the white dwarf, slightly increasing its mass with each eruption. Importantly, SS CYG will not explode as a supernova because the masses involved are far less than those required to reach that threshold. Observation of the light curve of SS Cyg (Figure #1) reveals alternating intervals of broad and narrow eruptions, lasting approximately 18 and 8 days respectively.

SS CYG also exhibits occasional anomalous eruptions, generally rare, broad, and symmetrical, characterized by a slow ascent rate. Although the star has generally exhibited this characteristic of variable flares since its discovery, SS Cyg experienced a period of "confusion" between 1907 and 1908, during which it ceased to display its normal flare behavior and underwent only slight fluctuations.

Cannizzo (1993) suggested that the determining factor for the nature of a flare (narrow or broad) depends on the mass present in the disk at the onset of a thermal instability. Thus, a narrow flare could correspond to a moderate mass transfer, while a broad flare could be induced by a significant mass transfer.

Figure 2 - SS CYG : BBC – Sky ant Night Magazine - https://www.skyatnightmagazine.com/advice/ss-cygni

Artistic representation of the SS Cygni binary system, with accretion disk and matter transfer.

The Astrophysics of the Star

First and foremost, SS Cygni is a non-magnetic binary. This is important because if the white dwarf had a strong magnetic field (polar type), there would be no complete accretion disk, and therefore no disk "flashes"!

Secondly, the eruptive behavior of SS Cygni is well described by the Disk Instability Model (DIM), in which the progressive accumulation of matter in the accretion disk leads to an abrupt transition between a cold, low-viscosity state and a hot, ionized, and highly viscous state. This transition triggers a thermal wave that propagates through the disk, significantly increasing the system's luminosity. The frequency and duration of the flares depend on the mass transfer rate, the mass of the white dwarf, and the viscosity parameter α. In the case of SS Cyg, the broad and narrow flares could reflect variations in the mass transfer rate from the red dwarf, possibly modulated by the latter's magnetic activity.

There's a fundamental physical concept at play here: the virial theorem. In theory, the boundary layer should emit as much energy (50%) as the entire accretion disk (50%). That's a massive energy source!

When we talk about the "boundary layer," we're referring to another part of the anatomy of cataclysmic stars, also called the "flash" or the "hot point"—the place where matter touches the accretion disk. I asked an astrophysicist what exactly we see when we look at the star: the red dwarf? The white dwarf? Or the accretion disk?

He told me it was this flash, an ultra-hot transition zone located between the inner edge of the accretion disk and the surface of the white dwarf. It's the main driver of X-ray emission in cataclysmic variables. Furthermore, the flash doesn't originate from a nuclear reaction (unlike a nova), but from a sudden release of heat. For weeks, the disk accumulates gas like a dam filling up. When the temperature rises slightly, the gas becomes ionized, its viscosity explodes, and the "dam" breaks. The "flash" we see is the gravitational energy of all this matter falling suddenly toward the star and violently rubbing against the disk.

The flash doesn't ignite everywhere at the same time:

-

The "Inside-out" flash: Sometimes, the instability starts near the white dwarf and spreads outward from the disk.

The "Outside-in" flash: This is the most common type for SS Cyg. The instability begins at the outer edge of the disk. The visible light flash occurs first, then moves toward the center.

The grand finale: When this flow of matter finally reaches the surface of the white dwarf, we get the X-ray flash in the boundary layer that we discussed earlier.

This is a sustained flash: as long as the disk hasn't emptied and cooled, it continues to shine intensely.

Once the disk becomes too empty, the temperature drops, the gas becomes neutral (less viscous), and the star "goes dark" to return to its resting state.

In short, in the Nova Dwarf (SS Cyg), it's the disk that lights up!

| Component |

At Rest (Quiescence) |

Outburst |

|

The Accretion Disk |

Dominant (especially blue/UV) |

crushes everything (95%+ of the light) |

|

The Red Dwarf |

Visible (especially in the Red/IR range) |

Completely drowned |

|

The White Dwarf |

Very difficult to see (hidden by the disc) |

Invisible |

The thermal instability of the disk

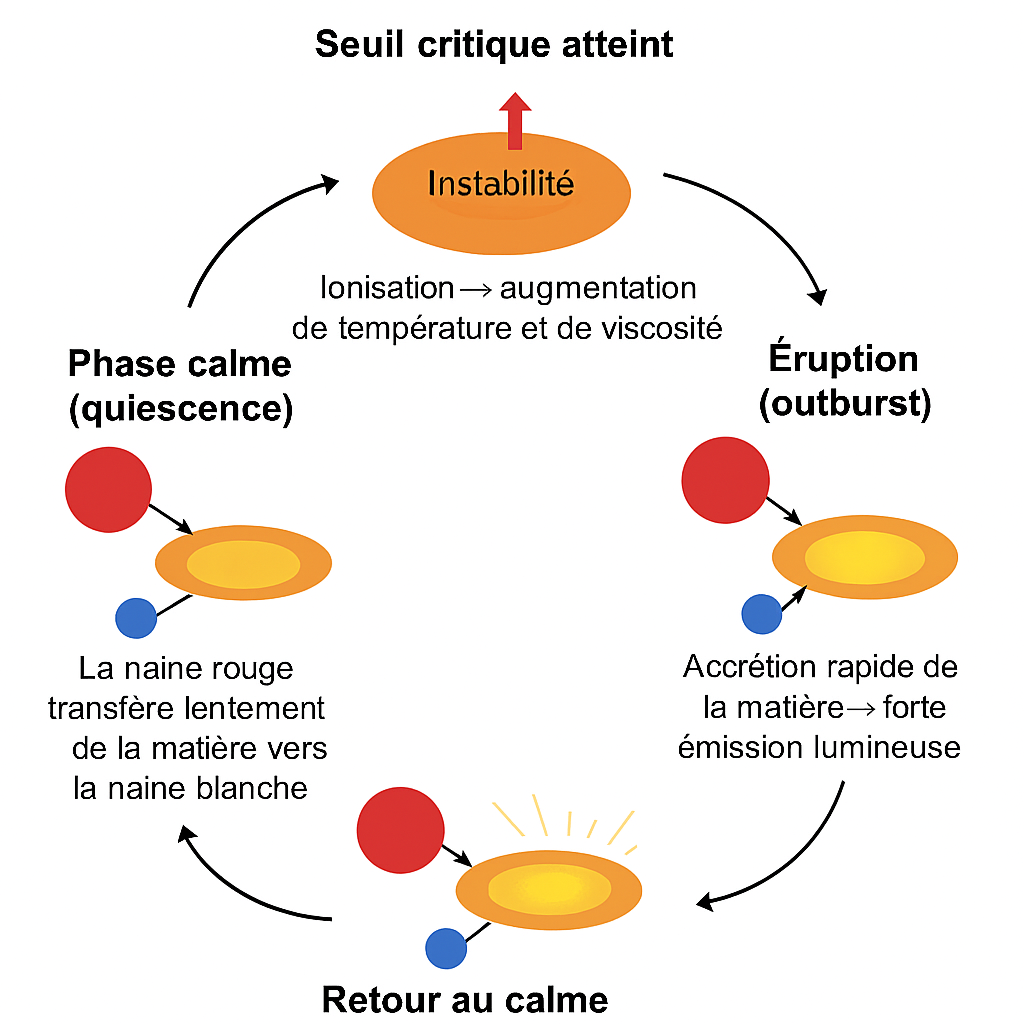

Figure 3- Courtesy of Copilot AI

- Resting state: Gas accumulates in the disk, but viscosity is low. The disk is "cold" and dim.

- Triggering: When the critical density is reached, hydrogen ionizes. This causes a sudden increase in viscosity.

- Burst: Matter falls massively toward the white dwarf, releasing a colossal amount of gravitational energy in the form of light (gain of 3 to 4 magnitudes).

- Narrow vs. Wide Bursts (Asymmetry of light curves)

- Narrow bursts: Rapid rise, rapid decline.

- Wide bursts: The plateau of brightness lasts longer.

- Cycles: Although the star's orbital period is 6.6 hours (0.275 days), the average interval between bursts is about 50 days and is variable.

Optical/X-Ray Correlation

- During its resting state, it emits hard X-rays.

- During the burst, the hard X-ray flux often drops while the soft X-ray flux increases, because the inner disk is "crashed" against the white dwarf.

A word about photometry.

Rapid variations: Flickering

The rapid variations you see in a B-filter (often on timescales of a few seconds to a few minutes) are not the "flash" (the burst) itself, but what is called flickering.

This is not due to the overall eruption, but to two very localized phenomena:

The Hot Spot: This is where the jet of gas from the companion star hits the edge of the disk. It is an area of extreme turbulence. Imagine a high-pressure jet of water hitting a rotating disk: it creates constant turbulence and flashes of light.

Internal turbulence: The disk isn't a smooth fluid; it's full of "clumps" of magnetized gas colliding with each other.

Why the B filter? Because these phenomena are very hot. Blue (B) and ultraviolet light capture this "agitated" thermal energy much better than red.

Spectroscopy

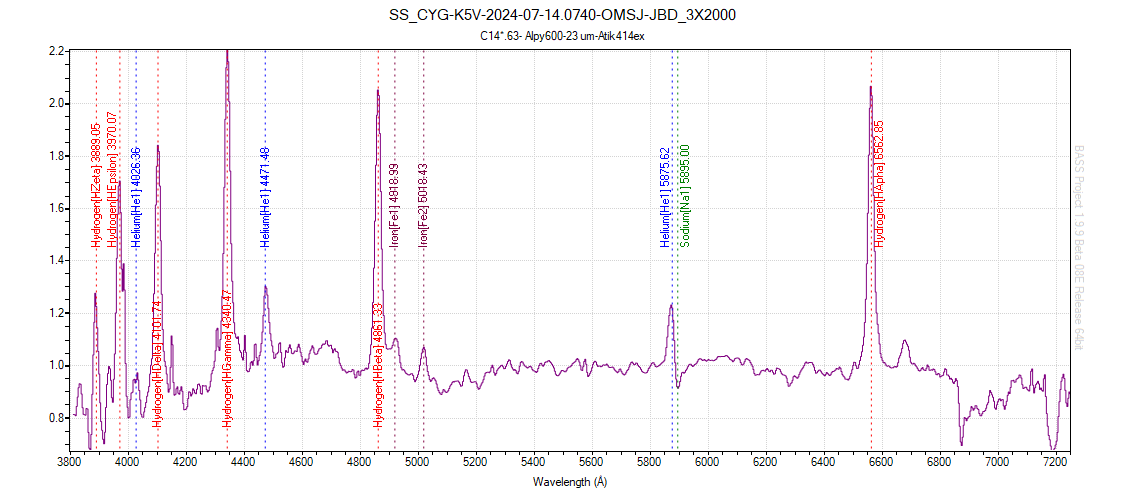

Figure 4- Spectre de SS CYG, basse résolution au Alpy-600 - Juillet 2024

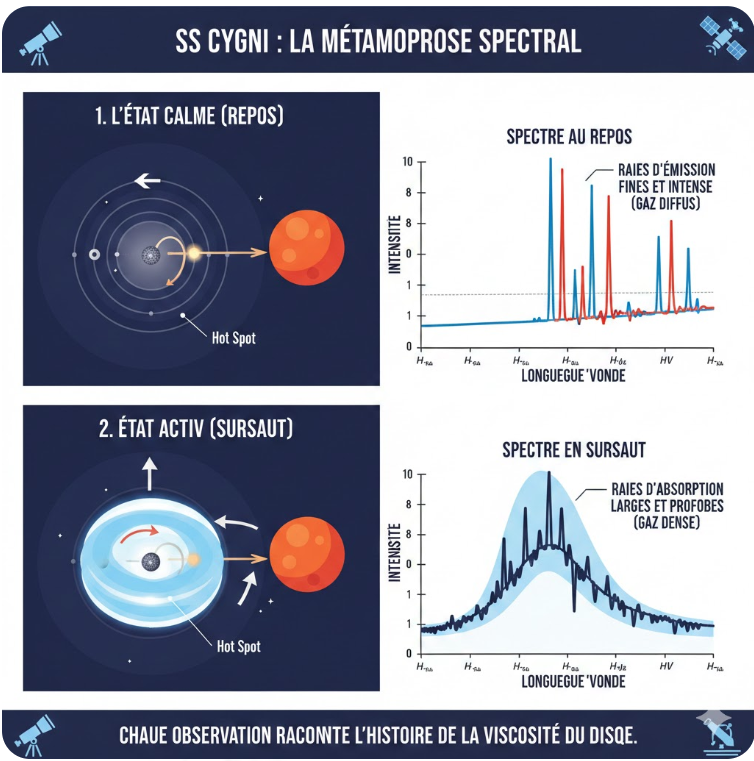

From a spectroscopic perspective, SS CYG exhibits a predominantly emission spectrum with well-represented Balmer lines, particularly during eruptions. Some P Cygni profiles are also visible due to the winds and the high velocity of the two bodies in the system. Elements such as helium, sodium, and iron are also present.

The spectrum displays unique disk characteristics: broad lines (rotational broadening) and occasionally pairs of narrow absorption lines exhibiting orbital behavior, indicating complex structures or eclipses within the disk.

Figure 5 - Courtoisie Gemini IA

At rest: Very bright and narrow hydrogen emission lines (Balmer lines) are visible. They originate from the hot, low-density gas of the disk. They are often "double" (cowhorn lines) due to the disk's rotation (Doppler effect: one side approaches, the other moves away).

During an eruption: The disk becomes so dense and hot that it behaves almost like a stellar surface (a black body).

- The Balmer lines no longer necessarily "shine" in emission; they often become broad absorption lines (as in a normal A-type star).

- The "exploding disk" creates such intense gas pressure that the lines broaden (Stark broadening). This indicates that mass transfer has become massive.

Conclusion

SS Cygni remains a fascinating natural laboratory for studying binary interactions, accretion disks, and thermal instabilities. Its proximity, brightness, and regularity make it a prime target for both amateur and professional astronomers. It perfectly embodies the richness of cataclysmic stars and the importance of collaboration among observers worldwide.

References :

- Warner, Brian. Cataclysmic Variable Stars . New York : Cambridge UP, 1995. ISBN 0-521-41231-5.

- Coel Hellier. Cataclysmic variable Stars – How and Why They vary : Springer, Praxis Publishing.

- Smak (1999) - Dwarf Nova Outbursts - https://acta.astrouw.edu.pl/Vol49/n3/pap_49_3_7.pdf

- Cannizzo, John K., et Janet A. Mattei « A Study of the Outbursts in SS Cygni ». The Astrophysical Journal https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/306165

- SS CYG – AAVSO: https://www.aavso.org/vsots_sscyg#:~:text=SS%20Cygni%20Takes%20the%20Stage,to%20fame%20was%20not%20predicted.

- John K. Cannizzo and Janet A. Mattei (1998) – “A Study of the Outbursts in SS Cygni” - https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/306165

- Sterne, T. E., and L. Campbell "Properties of the Light Curve of SS Cygni." Annals of the Observatory of Harvard College, 90, 1934, 189.

- An optical time-resolved spectroscopic study of SS Cygni. II. Outburst. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1996A%26A...308..833M/abstract

- The Disk Instability Model (DIM):

Lasota (2001) : The disc instability model of dwarf novae and soft X-ray transients

- The Evolution of X-rays and UV (Optical/X-ray Delay):

Wheatley et al. (2003) : The X-ray and extreme-ultraviolet evolution of the 1996 October outburst of SS Cygni

- Physical Parameters and Period (6.6 h):

Bitner et al. (2007) : The Masses and Evolutionary State of the Stars in the Dwarf Nova SS Cygni

- Long-Term Light Curve Analysis:

Cannizzo (1993) : The 10-20 day oscillations in the light curve of SS Cygni

JBD 2026