STARS, our raw material ...

When we look at the night sky, we see twinkling stars, the Sun, the Moon, and the planets performing their celestial dance against a steady backdrop of stars. To the casual observer, these stars appear perfect, stable, peaceful, serene, and unchanging. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth!

The Universe as we know it today is actually a very dangerous place, with dark clouds of dust and gas, atoms so cold they almost stop moving, and explosions so extreme that entire star systems are obliterated in the blink of an eye.

Stars, these massive balls of molten hydrogen, are factories that burn and fuse single hydrogen atoms into helium. These behemoths have illuminated the Universe for nearly 14 billion years.

Our Sun, which is also a star, is, by chance, a very stable star, balanced between the force of gravity trying to compress all the mass into a smaller sphere at the star's center and the force of nuclear combustion at the star's core trying to blow it apart.

Like a well-oiled engine, it has been burning its energy for 6 billion years and provides us with energy and heat for several billion more years. It consumes 4 million tons of hydrogen every second and releases as much energy as 10 billion nuclear bombs. (https://www.planetoscope.com)

But this isn't the case for all other stars: many are binary systems, others are so active that their faces are streaked, to the point that they appear to vary in intensity as they rotate (for example, BY DRA). Still others vary in pulsation, like Cepheids.

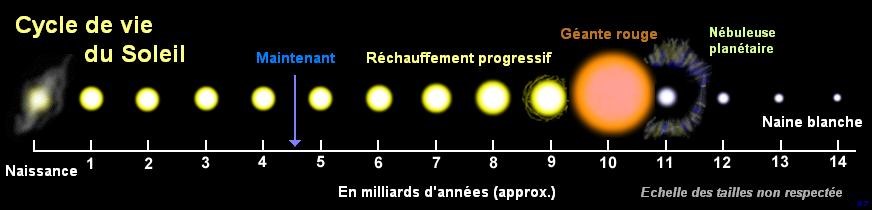

As a star evolves throughout its life, and as its life depends on another force on the scale, there are sometimes battles between these two gravitational forces that influence its behavior and also its end. If one or the other of these forces ultimately wins, the star then dies, either by shedding its outer layers and becoming a white dwarf (as our Sun will), or by exploding in space as a supernova.

Depending on its size and size, a neutron star or a black hole could also be its final state.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Évolution_stellaire

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Évolution_stellaire

In short, the Universe is filled with stars that vary greatly in their behavior, temperature, color, and size. It's a fascinating world, and it's helpful to have some basic knowledge about it, without delving into complex calculations, but simply to better understand our Universe.

These are just a few of the reasons why a star might vary or appear variable from our perspective on Earth. And there are many more. Every star has been, or will be, a variable in its light intensity at some point. It's inevitable. If you could only live long enough, you would see every star become a variable star. Our Sun will be no exception.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Évolution_stellaire

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Évolution_stellaire

To know our place in the cosmos, we must understand the stars.

To know the stars, we must understand their lives.

(Classification of Variable Stars and Manual of Light Curves 2.1)

|

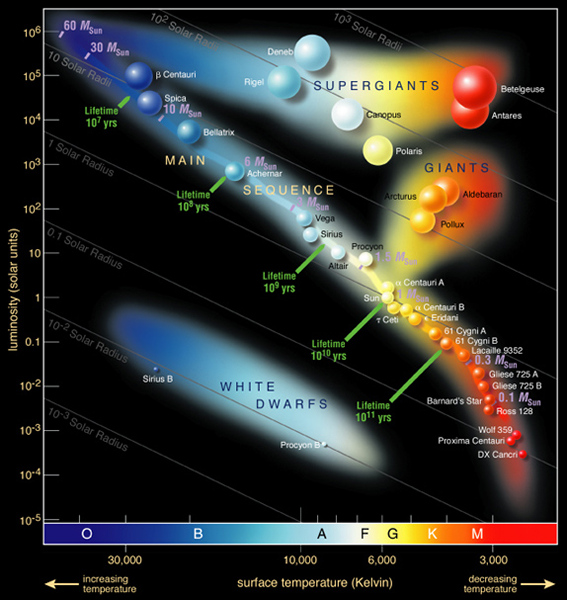

Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram The Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (or H-R for short) is a fundamental concept in astronomy. It's an image that summarizes the major classes of stars and their positions relative to their main sequences, representing their active life according to their characteristics. It also allows us to study stellar populations and understand the theory of stellar evolution. |

|

Each class is subdivided into 10 subclasses, from '0' to '5' for type O, and from '0' to '9' for the other spectral types except S, which is undivided, and N, which is divided from '1' to '3'. These divisions allow for more precise classification. The classification criteria are based on spectroscopic lines and their relative intensities, which are related to the temperature in the region of the star where these lines are formed.

| Type Spectral | Température (K) | Type spectral | Éléments prédominant |

|---|---|---|---|

| O | > 20 000 | Hélium ionisé (He II) |

highly ionized elements: He II, Si IV |

| B | 20 000-10 000 | Neutral helium, with hydrogen lines known to appear | Neutral helium, hydrogen: Raie de Balmer |

| UNE | 10 000-7 000 | Neutral hydrogen lines (Balmer series) clearly visible | Especially hydrogen, the Balmer line Appearance of the H and K lines of ionized calcium. |

| F | 7 000-6 000 | Ionized calcium (Ca II) is visible while the hydrogen lines weaken | Primarily H and K lines of ionized calcium. Enhancement of the lines of ionized metals T1 II, Fe II. Hydrogen lines: Balmer series. |

| g | 6 000-5 000 | Ionized calcium (Ca(II)) predominates, hydrogen lines are very weak, and metallic lines such as iron appear. | Primarily the H and K lines of ionized calcium and the metallic lines of CaI and FeI. Balmer series. Appearance of the CH and CN molecular bands |

| K | 5 000-3 500 | Neutral metals (Ca, Fe) dominate; molecular bands are visible. | Mainly H and K lines of ionized calcium, strengthening of neutral metal lines and CH and CN molecular bands and especially Ti O. Remnants of ionized metal and hydrogen lines. |

| M | 3 500-2 000 | The molecular bands are clearly visible, especially those of titanium oxide (TiO) |

Mostly TiO₂ molecular bands |

| S | 2 500 | Zirconium Oxide | Excess of heavy elements, molecules of ZrO, YO, KaO |

| R | 2 000 | Carbon | Strong CN features, and C2 features increasing in strength. Often catagorized as a C (Carbon) star. |

| N | 1 500 | Composés du carbon | C2 present, with CN decreasing in strength. Often catagorized as a C (Carbon) star. |

* The study of spectral lines allows us to estimate the temperature and pressure in the lower atmospheres of most stars, from types O to M. On a [specific] basis, complete this sequence of spectral types with others as follows:

W - O (RN) - B (S) - (Be) - A - F - G - K - M - L - T - Y

* W-type stars concern Wolf-Rayet stars (discussed in a separate article soon)

* R and N-type stars are called "Carbon-type" because their spectra show the bands of the carbon molecule.

* S-type stars are characterized by zirconium oxide bands.

(Reference: Agnes Acker - Astronomy and Astrophysics 5th edition - Dunod Edition - p. 142)

Finally, some classes, particularly supergiants, can be subdivided into subclasses denoted 'a', 'ab', or 'b'. The complete classification (Kitchin 1995) is:

| I, Ia, Iab, Ib | Supergiant stars (class 0 is sometimes used for truly exceptional stars like P Cyg) |

| II | Bright giant stars |

| II-III, IIIa, IIIab, IIIb, III-IV | Giant stars |

| IV | Subgiant Stars |

| V | Stars of the main series |

| VI | Subdwarf stars |

| VII |

White dwarf stars |

Specific criteria

To meet the very specific criteria of certain stars, a final suffix is sometimes added to the spectral class to indicate a particular characteristic; here is a list of the main codes used (Kitchin 1995):

| comp | Spectral mixing: two types of spectra are mixed indicating the presence of an unresolved binary star. |

| e | Indicates at least one emission line. If hydrogen lines are seen, a Greek letter can indicate the last visible hydrogen line. For example, "e γ" if H γ is the last visible line of the Balmer series. |

| m | Strong metallic lines seen abnormally (often applied to A-class stars). |

| n | Visible absorption lines due to rapid rotation. |

| nn | Highly visible absorption lines due to very rapid rotation. |

| Nebraska | The spectrum of a nebula is mixed with that of the star. |

| p | Unspecified characteristics except in the case of A-class stars which exhibit anomalous intense metallic lines. |

| s | Presence of very fine lines. |

| sh | B- to F-class stars exhibiting emission lines from a gas envelope. |

| var | Variable star spectrum. |

| wl | Faint metallic lines from a dim star. |

Star rating

https://sites.uni.edu/morgans/astro/course/Notes/section2/spectraltemps.html

Spectral Types - contribution: Sylvain Rondi

http://www.astrosurf.com/aras/spectypes/spectypes.htm

Agnes Acker - Astronomie Astrophysyque 5ème édition - Édition Dunod

* The source for several of the texts is an adapted translation of the AAVSO's "Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual 2.1".

It was translated and adapted with their permission and is also referenced by them.

JBD-2020