Classification of eclipsing variables

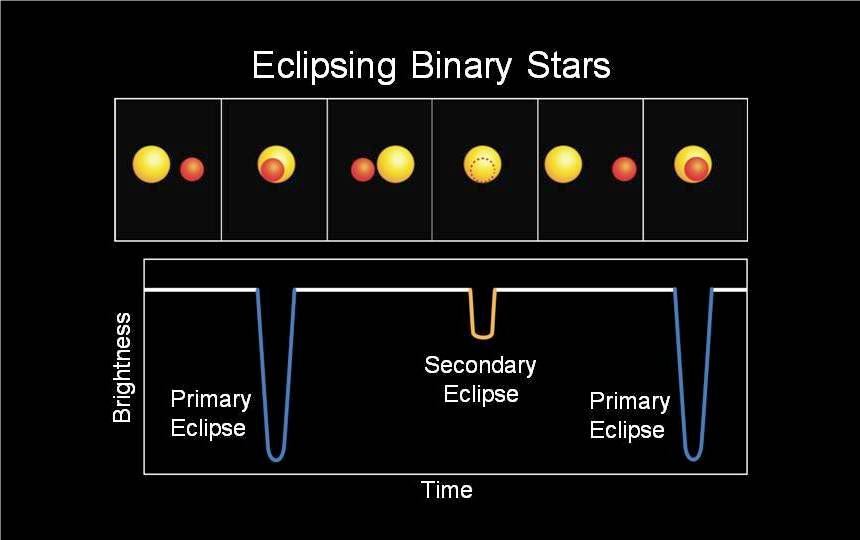

Eclipsing variables (E) are close binaries whose orbital plane coincides with our line of sight. When one star passes in front of the other, it eclipses the light of the former, causing a dip in brightness as it passes. When the fainter star passes in front of the brighter star, since it blocks its flux, this is the primary eclipse. Subsequently, the brighter star can also pass in front of the fainter one, resulting in a secondary eclipse. The interval between primary eclipses is equal to the orbital period of the system.

Credit: AAVSO

Binary systems are interesting for many reasons. It is estimated that more than half of all stars are actually binary or multiple star systems, and their origins are still not well understood. There are likely several different scenarios by which these systems could have formed. The fact that the components of eclipsing binary systems are close to each other can affect how the individual stars evolve. The light curves of ecliptic binaries provide important clues for determining the physical properties, such as the size, mass, luminosity, and temperature of the stellar components.

Algol Aa2 orbits Algol Aa1. [1]

This animation was created from 55 images of the CHARA interferometer in the near-infrared H-band, sorted according to orbital phase.

Because some phases are not covered in the animation, Aa2 appears intermittently.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algol

_______________________

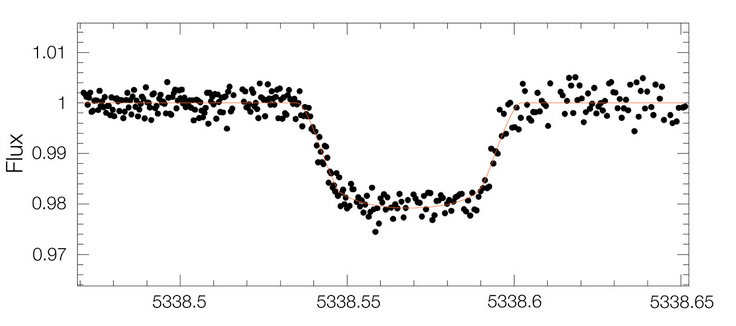

Algol variables (EAs) are eclipsing systems containing spheres or slightly ellipsoidal components. The precise times of the beginning and end of the eclipses are well defined by their light curves. It should also be noted that secondary eclipses may be absent. Their light curve profiles are essentially flat between eclipses and can vary slightly due to the ecliptic shape, the physical variability of the components, or due to reflection effects. Orbital periods range from 0.2 to over 10,000 days, and the amplitudes of variation can reach several magnitudes.

* Reflection Effect

If the axes of two stars diverge very closely from our perspective, some of the energy from each star will influence that of its companion, be absorbed, and then re-emitted. The part of the star facing its companion is hotter and therefore slightly brighter than the part facing away. Calling this phenomenon "reflection" is somewhat misleading. The effect is most noticeable just before the eclipse of the cooler, and therefore paler, star. The result produces "shoulders" in the light curve of the secondary eclipse.

An Algol (EA) type light curve (Credit: AAVSO)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algol [2]

_______________________

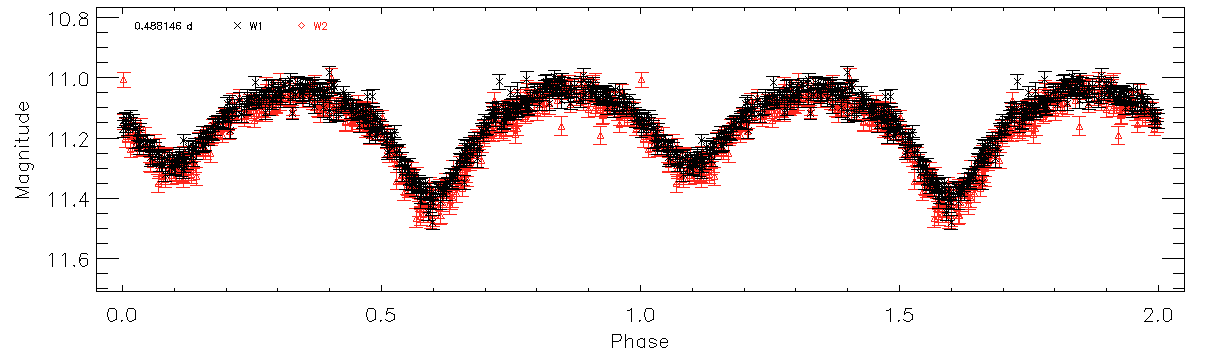

Beta Lyrae (EB) type variables are eclipsing variables that also contain ellipsoidal components. The exact times of onset and end of the eclipse are impossible to determine, as the system's brightness varies continuously. There are always secondary minima. The depth of these secondary eclipses is usually less pronounced than that of the primary eclipse. Their periods are generally longer than one day, and the amplitude of the light changes can be as great as two magnitudes in V-filters. The stars in the system are typically of spectral types B and A.

It is worth mentioning here that the Beta Lyrae type is such a bizarre case that it should not be considered the prototype for any class of variable stars.

Beta Lyrae:

"The current understanding of Beta Lyrae is that it is an eclipsing binary in a mass transfer phase between its components. The star losing mass is a B6-8II object, with a mass of about 3 solar masses (M<sub>S</sub>), which is filling its Roche lobe and sending material to its more massive companion at a rate of about 2 × 10<sup>-5</sup> solar masses (M<sub>S</sub>) year<sup>-1</sup>, leading to the observed rapid increase in the orbital period at a rate of 19 seconds per year. The star gaining mass is the first B star, with a mass of about 13 solar masses (M<sub>S</sub>).

It is completely hidden within an opaque accretion disk, jet-like structures perpendicular to the orbital plane, and a light-scattering halo above the star's poles. The observed radiation from the disk corresponds to an effective temperature much lower than that which would be expected from an older B star." The disk shields the radiation from the central star in directions along the orbital plane and redistributes it in directions perpendicular to it. This is why the star that is losing mass appears as the brighter of the two in the optical region of the spectrum.

Currently, fairly reliable estimates of all the basic properties of the binary and its components are available. However, despite significant progress in understanding the system in recent years, some disagreement remains between existing models.

(From Harmanec, P. (2002) "The ever-challenge emission line binary Beta Lyrae", AN, 323, 87-98.)

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1521-3994(200207)323:2%3C87::AID-ASNA87%3E3.0.CO; 2-P / abstract

In short... They're fascinating!

_______________________

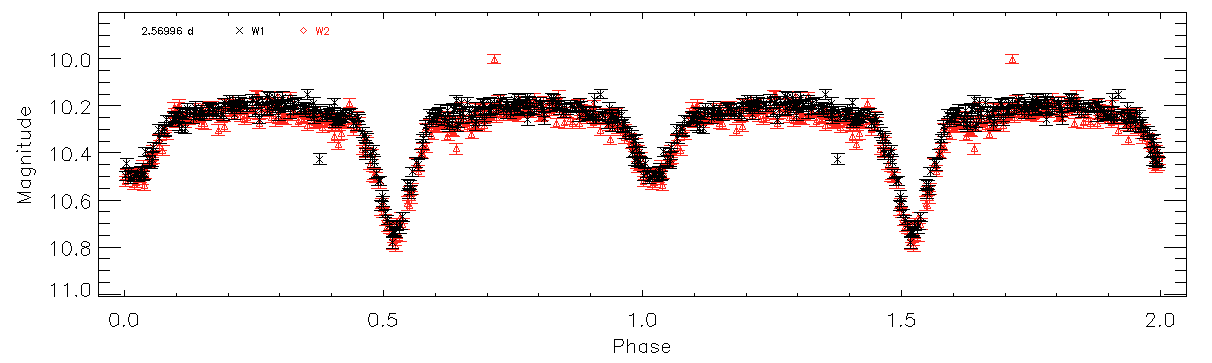

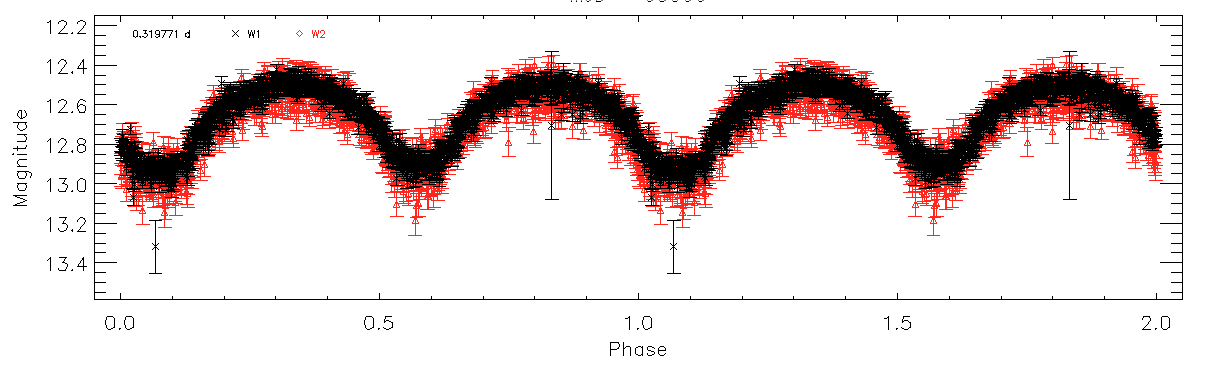

W Ursae Majoris (EW) type variables are eclipsing variables that also contain ellipsoidal components, but they are almost in contact as they orbit around a common center of mass. Like Beta Lyrae (EB) variables, the exact times of onset and end of eclipse are impossible to determine because the system's brightness varies continuously. The depths of the primary and secondary eclipses are almost equal. Orbital periods are usually reduced to one day, and variability amplitudes are typically reduced to 0.8 magnitudes in V-filters. The components are generally of spectral types F and G. [3]

Light curve of a typical variable butterfly of the type W Ursae Majoris (EW) (Credit: AAVSO)

*KIC 9832227 is a good example.

_______________________

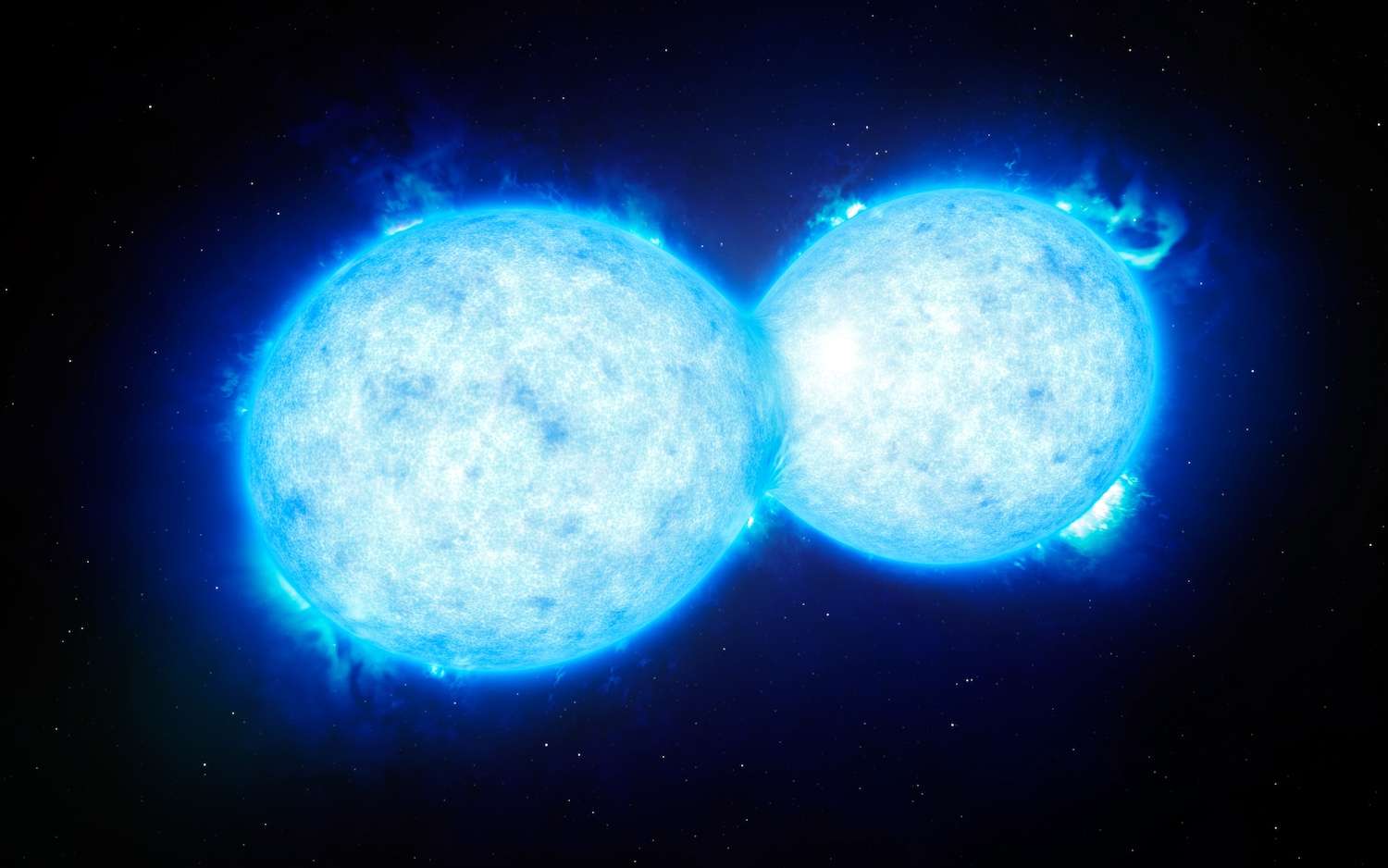

Transient variables (TPs) of exoplanets are stars whose infinitesimal variations in light are caused by the eclipse of one or more of their planets as they transit between the star and our viewpoint. An article on tracking exoplanet transits will be available soon.

The light curve of an exoplanet transiting in front of its parent star, WASP-19b

Image credit: TRAPPIST / M. Gillon / ESO

_______________________

Roche Lobe

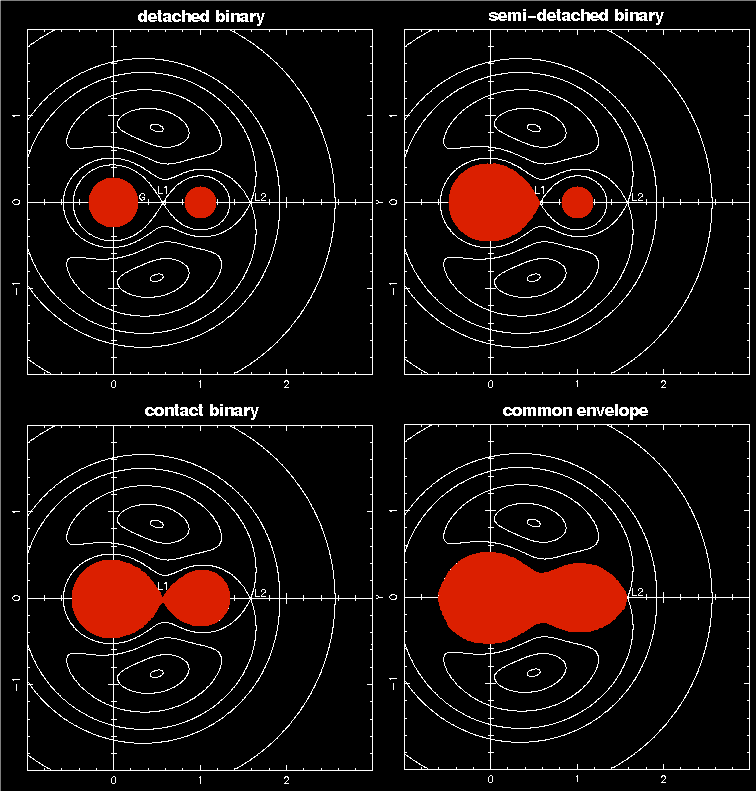

Modern classification schemes for binaries, including eclipsing binaries, are based on the concepts of Roche lobe and Lagrange points. The Roche potential takes into account both gravitational and centrifugal forces. Roche lobes are named after the French astronomer and mathematician Édouard Roche, who introduced this concept in 1873. [4]

Detached binaries are systems where both components are well within their Roche lobes. The stars remain nearly spherical, and tidal distortion is minimal.

Semi-detached binaries are systems where one star fills the Roche lobe and is distorted. There is likely mass loss through accretion at the inner Lagrange point of its companion star.

Contact binaries occur when both stars fill their Roche lobes and are essentially in contact with each other. In some cases, a common envelope of matter that obliterates the distinction between individual stars can also surround the pair. These are often called common envelopes or contact binaries.

Roche geometry diagrams of different binary systems

_______________________

Suggested reading:

[1] Algol-type stars

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algol

[2] Type Beta Lyrae

https://www.aavso.org/vsots_betaper

[3] VSOTS W Ursae Majoris (EW)

http://www.aavso.org/vsots_wuma

[4] Rock Lobe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roche_lobe

* The source of several of the texts is an adapted translation of the book "Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual 2.1" by the AAVSO. It was translated and adapted with their permission and is also referenced by them.