Article en Français

Pulsating variables

First, it's important to distinguish between two types of pulsations: radial and non-radial.

When we talk about radial pulsation, we're referring to the symmetrical, spherical expansion and contraction of a star's outer layers. Visually, it's like blowing up a balloon and then slowly letting the air out. The volume of the balloon (or star) increases and decreases cyclically.

* Large pulsating variables vary in amplitude in this way—Cepheids, Miras, and RR Lyrae—pulse primarily in radial mode.

The pulsation is non-radial when the star changes shape but not volume. Imagine our water-filled balloon. If you take it by one end and squeeze it, the balloon shrinks under the pressure of your fingers and expands outward at the other end. However, it still holds the same amount of water. The volume hasn't changed, only the shape.

Non-radial pulsation tends to produce smaller amplitudes of variation, such as those observed in B stars and white dwarfs. Some stars, like Beta Cephei and Delta Scuti, vibrate in both radial and non-radial modes, so both types can be found in the same stars.

Cepheids

The explanation for the pulsation of Cepheids, and other similar types of variables, lies in the phenomenon known as the Eddington valve. Helium is the gas that makes this possible. This is why it is present in stars that are generally older. They have used up all their hydrogen and are now burning helium in their outer layers.

Doubly ionized helium is denser than single-ionized helium. Since radiation from the stellar core cannot escape efficiently, it is absorbed and causes even more ionization. The more helium is heated, the more ionized it becomes. Thus, during the darkest period of a Cepheid's cycle, the ionized gas in the outer layers is heated by the star's radiation, and as the temperature builds up, the star begins to expand. As it expands, the layer cools, becoming less ionized and therefore more transparent, allowing radiation to escape. Then the expansion stops, and the contraction stabilizes due to the star's gravitational pull. And... the process repeats.

Some pulsating variables are very strictly periodic and as predictable and regular as clockwork. Other pulsating stars are less so, while others are only semi-regular. In fact, these are what we call semi-regular variables!

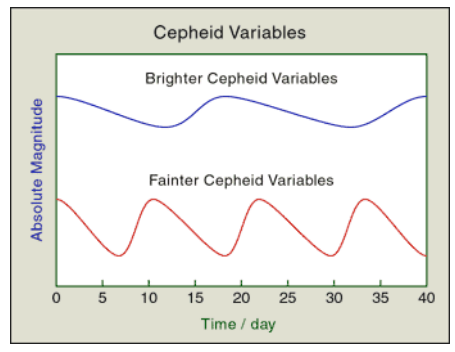

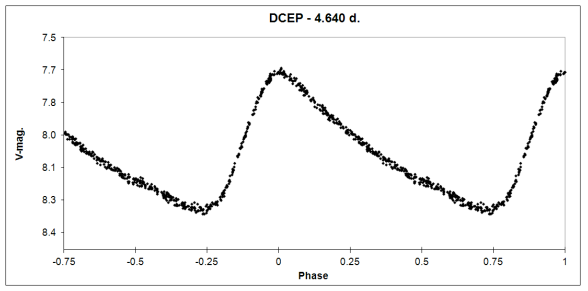

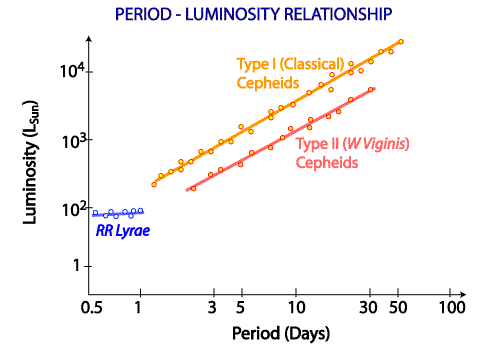

Classical Cepheids (DCEPs) are bright yellow, very luminous, supergiant, and pulsating. Their amplitudes range from a few hundredths of a magnitude to two magnitudes in V-filter mode, and their period from 1 to 135 days. Their variability is strictly regular and over very long periods. At their maximum period, their spectral type is F, and at shorter periods, from G to K for the longest. The more luminous a Cepheid variable star is, the longer its period of brightness variation.

Classical Cepheids are probably the most famous and important pulsating variables. They are luminous, numerous, and generally have large amplitudes, so they are easily visible to astronomers throughout our galaxy and can even be observed in other galaxies in our Local Group, such as the Magellanic Cloud, M31, and M33. Because of the well-known period-luminosity relationship, they have been used as the standard candles upon which our understanding of distances in the Universe has been built.

See also VSOTS Delta Cepheid Http://www.aavso.org/vsots_delcep

Type II Cepheids pulsate for the same reasons as classical Cepheids, and it is difficult to distinguish them solely by their light curves. Their physical nature and evolutionary history are quite different. Population II, these Cepheids are older and have low masses, ranging from 0.5 to 0.6 solar masses. They tend to reside away from the galactic disk and have higher metal concentrations than classical Cepheids, making them important "fossils" of the first generation of stars in our galaxy. Type II Cepheids obey a different period-luminosity relationship. As with classical Cepheids, their spectral type is F at their maximum luminosity, and at their minimum, they range from G to K.

Once this error was discovered and the period-luminosity model for Cepheids was recalibrated in the 1950s, the scale of distances in the Universe was doubled!

W Virginis (CW) type stars vary in brightness from 0.3 to 1.2 magnitudes in V, and have periods ranging from 0.8 to 35 days. The light curves of CW stars sometimes show bumps on the downward branch of the light curve, or occasionally exhibit a large maximum plateau.

W Virginis type variables are further subdivided into CWA and CWB. CWA stars have periods longer than 8 days, while CCB stars, also known as BL Herculis type stars, have periods of 8 days or less.

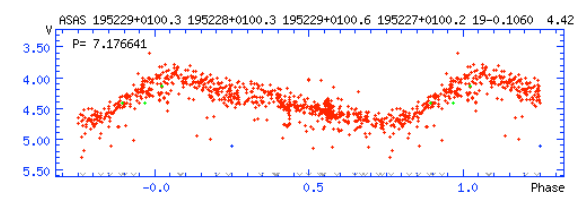

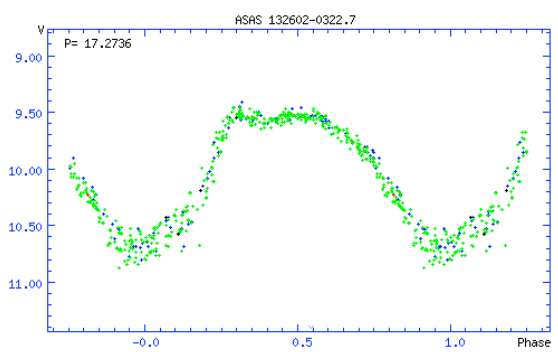

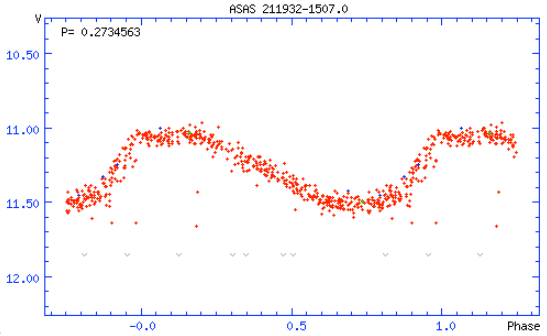

La courbe de lumière ASAS progressive de BL Herculis

Additional recommendations: VSOTS W Virginis

http://www.aavso.org/vsots_wvir

______________________________________________

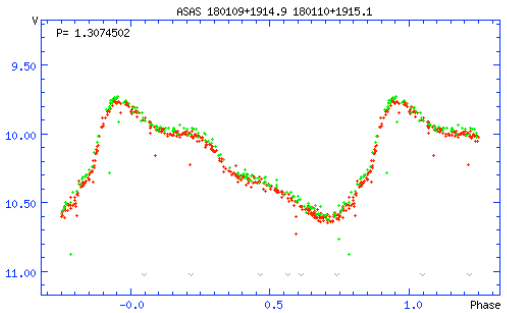

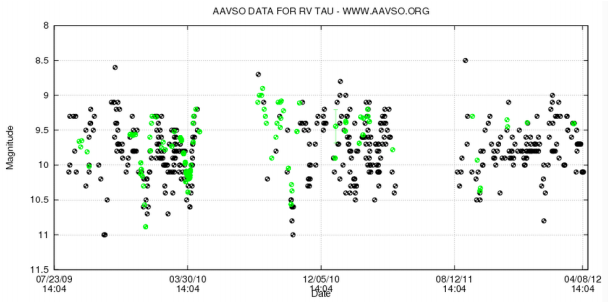

RV Tau stars are yellow supergiant stars whose light curves exhibit alternating deep and shallow minima. The period between one deep minimum and the next varies from 30 to 150 days. The amplitude of this variability can be 3 to 4 magnitudes in V-filters. Like classical Cepheids, their spectral type is F at their maximum brightness, and at their minimum, they vary from G to K.

They are subdivided into RVA and RGB types. RVA stars are those that do not vary in average amplitude (example: AC Her). RGB stars are RV Tau stars that vary in average amplitude by up to 2 magnitudes in V-filters, with periods of 600 to 1500 days. (Examples: RV Tau, DF Cyg)

Highly recommended lecture:

VSOTS RV Tauri http://www.aavso.org/vsots_rvtau

______________________________________________

RR Lyrae stars are fast pulsating variables with periods ranging from 0.1 to 1 day and amplitudes up to magnitude 1.5 in V-filters. They are spectral types A5 to F5 and have masses equal to about half the mass of the Sun. They are old stars that have exhausted almost all the hydrogen in their cores and are now burning helium. RR Lyrae stars are numerous in some globular clusters and were once nicknamed "cluster variables." They are imported into astronomy in the same way as Cepheid variables, in that they help us calibrate the distance to objects in the Universe.

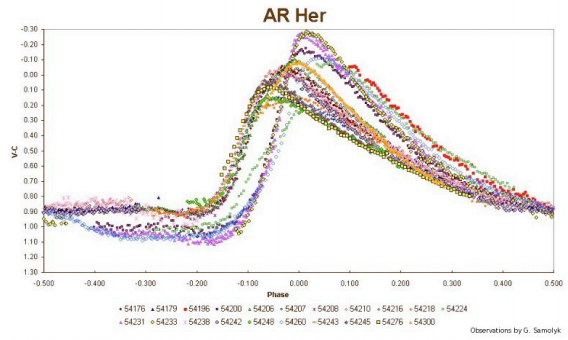

In 1916, Harlow Shapley discovered that the light curve of RR Lyrae stars was modulated in both amplitude and curve, with a period of about 41 days. This modulation became known as the Blazhko effect, the explanation of which remains one of the mysteries to be solved in astrophysics.

Suggested lectures:

VSOTS RR Lyrae http://www.aavso.org/vsots_rrlyr

http://physique.unice.fr/sem6/2013-2014/PagesWeb/PT/Lyrae/cestquoieffetblazhko.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RR_Lyrae_variable

Courbe de lumière de AR manifestée la modulation dans la courbe de lumière de cette étoile connue de RR Lyrae

RR Lyr type stars are divided into subclasses RRAB, RRC, and RRD.

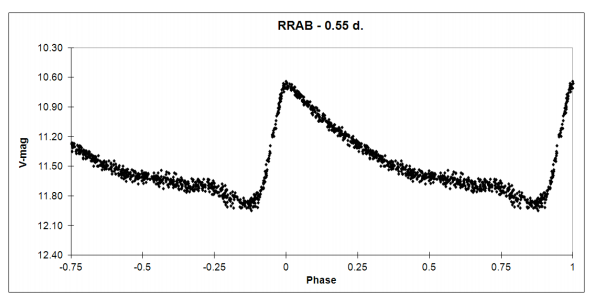

RRAB stars are variables with asymmetrical light curves and steep ascending branches. They have periods of 0.3 to 1.2 days and amplitudes ranging from 0.5 to 2 magnitudes in the V spectrum.

Une excellente courbe de lumière représentative d'une étoile RRAB

CRRs are variables with almost symmetrical light curves. Periods range from 0.2 to 0.5 days and variation amplitudes not exceeding 0.8 magnitudes in V.

Courbe lumineuse de YZ Cap et étoile RRC

We speak of RRD when we observe the superposition of the two modes above; we then observe a period ratio of 0.74 days and a fundamental period of approximately 0.5 days.

* On RRB callers in the GCVS.

______________________________________________

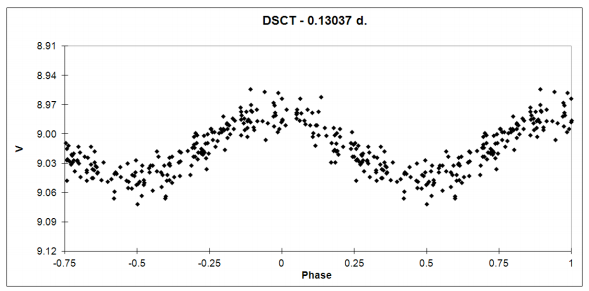

Une courbe de lumière delta Scuti. Notez la période très courte.

Delta Scuti stars (DSCTs) are the most numerous pulsating variables among all bright stars. The pulsation mechanism for DSCTs is well understood. It is fundamentally the same as for Cepheids. They are spectral types A through F, have short periods ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 days, and amplitudes ranging from 0.003 to 0.9 in the V spectrum. Many of these stars are multi-periodic. FG Virginis, for example, pulsates in 79 different modes! Including their small amplitudes makes analyzing their periods very difficult.

Period changes can be measured, making them a class of objects of interest to be monitored by AAVSO observers. DSCTs with amplitudes greater than 0.2 magnitudes are called high-amplitude Delta Scuti stars, or HADS.

Recommended reading: VOSS Delta Scuti:

http://www.aavso.org/vsots_delsct

______________________________________________

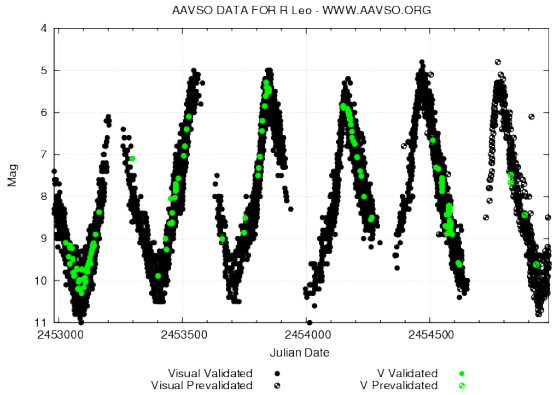

Mira (M) type variables are named after the star Omicron Ceti (aka Mira) and are relatively stable with periods of 100–1000 days, most ranging from 150 to 450 days.

They are red giant stars in the final stages of their stellar evolution.

Spectral amplitudes can range from magnitude 2.5 to 10. With such amplitudes, they have historically been the most numerous stars observed in the AAVSO program.

They are generally cooler, larger, and more luminous than red giants.

There are two reasons for the extreme visual amplitudes of Miras. First, as the star dimmers, it also cools, thus emitting less total energy in the visible spectrum. But the most important reason is that as it cools, it forms TiO₂ molecules, which are extremely efficient at absorbing light in the V spectral band.

Miras are highly evolved stars with masses ranging from 0.6 to several times the mass of the Sun. Their radii can even be several times that of the Sun. If they were located in our solar system, their outer atmospheres would extend beyond Earth's orbit.

Recommended reading:

http://astronomia-spectro.weebly.com/miras.html

Mira 2: Http://www.aavso.org/vsots_mira2

RU Virginis: Http://www.aavso.org/vsots_ruvir

And Miras with period changes: Http://www.aavso.org/mira-variables-period-changes

* The following definitions are taken directly from the GCVS and VSX documentation.

______________________________________________

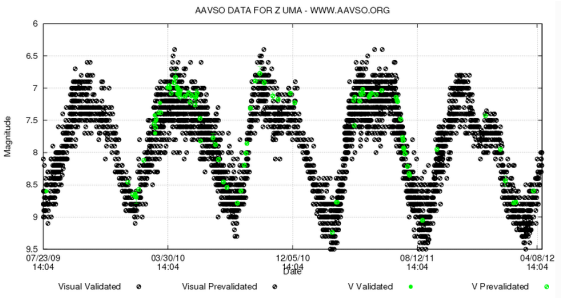

Semi-regular (SR) stars are giants or supergiants of intermediate and variable spectral types, exhibiting a notable periodicity in their light changes, accompanied or sometimes interrupted by various irregularities. Periods range from 20 to 2000 days, while the shapes of their light curves are quite different and variable, and amplitudes can range from several hundredths to several magnitudes (generally 1-2 mag in V).

______________________________________________

Based on the carbon-to-oxygen ratio at their surface, Miras stars are classified into three types: M, S, and C, equivalent to the types defined for normal red giants, and further categorized according to four period types.

(SRA) Semi-regular giants (M, C, S or Me, Ce, Se) whose periodicity is generally characterized by small light amplitudes (<2.5 mag in V). The amplitudes and shapes of the light curves generally vary, with periods ranging from 35 to 1200 days. Many of these stars differ from classical Miras stars by exhibiting smaller light amplitudes (Z Aqr).

(SRB) Semi-regular giants (M, C, S or Me, Ce, Se) whose cycle periodicity ranges from 20 to 2300 days, with intervals of slow, irregular, periodic changes. Some even have intervals of light constancy (Example: RR CrB, AF Cyg). Each star of this type can generally be assigned a certain average period (cycle); this value is given in the catalog. In a number of cases, the simultaneous presence of two or more periods of light variation can be observed.

(SRC) Semi-regular supergiants (M, C, S or Me, Ce, Se) with amplitudes of about 1 mag and periods of light variation from 30 to 1000 days (Mu Cep).

(SRD) Variable geometries and supergiants of spectral types F, G, or K, sometimes with emission lines in their spectra. The amplitudes of light variation fluctuate from 0.1 to 4 mags, and the period range is from 30 to 1100 days (SX Her, SV UMa).

Suggested reading:

VSOTS W Hya http://www.aavso.org/vsots_whya

VSOTS V725 Sagittarii http://www.aavso.org/vsots_v725sgr

Cepheids:

https://media4.obspm.fr/public/ressources_lu/pages_etalonnage-primaire/cepheides-apprendre.html

http://www.astronoo.com/fr/articles/cepheides.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cepheid_variable

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Eddington

* The source of several texts is an adapted translation of the book "Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual 2.1" by the AAVSO. It was translated and adapted with their permission and is also referenced by them.